About Monarchs, Migration, and Disease

North American monarchs are famous for undertaking the longest-distance two-way migration of any insect species in the world, traveling each fall from the U.S. and Canada to winter sanctuaries in the mountains of central Mexico. These iconic butterflies have captured the imagination of scientists and the public. In recent years, migratory monarchs have faced numerous challenges associated with a human activity including shifting weather patterns, changes in milkweed abundance and distribution, chemical insecticides, and roadway strikes.

Another obstacle monarchs face is a debilitating protozoan pathogen called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE) that develops inside the bodies of caterpillars. Infected adult monarchs emerge covered in millions of parasite spores, impairing their flight ability and reproductive success in addition to reducing their longevity.

Researchers at the University of Georgia are tracking the spread and impacts of the OE pathogen, in part through a citizen science project that empowers people across the country to take part in monarch monitoring and conservation efforts.

What is Project Monarch Health?

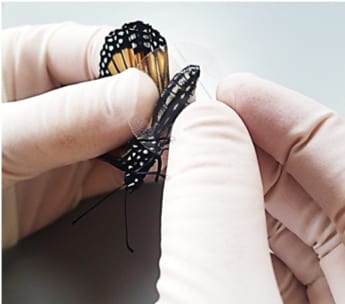

Monarch Health is a citizen science project based at the University of Georgia in which volunteers from across North America sample wild monarch butterflies to help track the spread of the OE protozoan pathogen over space and time. Citizen scientists test monarchs harmlessly for OE by pressing a clear sticker against the butterfly’s abdomen. Volunteers then send their samples to our lab at UGA for us to examine under a microscope for the presence of protozoan spores. Infected monarchs have many brown, football-shaped spores scattered in and around their scales. After processing samples, volunteers receive a summary of the infection status of each butterfly they monitored.

We also post season summaries of results on our program webpages, www.monarchparasites.org.

The broader mission of Monarch Health is to understand pathogen spread and impacts on monarch butterflies. We also aim to understand how disease patterns are changing in response to human activities, and what actions might mitigate disease spread. We seek to enhance awareness of monarch biology and conservation through the partnership of citizens and scientists.

Who Participates in Monarch Health?

Volunteers are essential to Monarch Health and other large-scale research projects on monarch butterflies. Monarch Health participants can be people of all ages and skills including families, retirees, classrooms, and nature centers. Since the project’s inception in 2006, over 1,000 volunteers from 43 U.S. states and 2 Canadian provinces have sampled 45,000 monarchs for Project Monarch Health.

Why this project matters:

There are many reasons to care about the future health of monarch populations. Monarchs and other insects like bees and moths are part of a diverse group of pollinators worldwide. Monarchs play a valuable role in science education and outreach, teaching children and adults about nature, metamorphosis, and migration. Many people have emotional and spiritual connections to monarchs. Recent research on the monarch genome showed that migrating monarchs have unique genes that enable them to fly long distances more efficiently. If migratory monarchs are lost, then these genes will disappear with them.

UGA researchers have found that the prevalence of the OE pathogen in wild migratory monarchs has nearly tripled since 2002. It is possible that this increase has been affected by human activities such as habitat loss and crowding, and future monitoring through Monarch Health can help scientists better understand why.